Recent news:

4000th facility has been added to the Ski Jumping Hill Archive

7000th ski jumping hill added to the Archive!

New Granåsen ski jump in Trondheim inaugurated

Fire destroys ski jumps in Biberau-Biberschlag

Copper Peak: Funding of the renovation finally secured

Send us your ski jumping hill photos and information via email!

Latest updates:

2025-02-22

2025-02-21

2025-02-20

Advertisement:

Partner:

Asker

Asker

Furubakken

Data | History | Hill records | Competitions | Contact | Links | Map | Photo gallery | Comments

.

Furubakken:

| K-Point: | 60 m |

Hill record: Hill record: |

60.0 m (Per Gjelten  , 1950) , 1950) |

60.0 m (Gudtorm Helldal  , 1959-01-18) , 1959-01-18) |

History:

At Asker, a city with 50,000 inhabitants with large suburban comunities, there have been ski jumping activities already since 1889 on several hills. At first Herklibakken at Semsvik was used for ski jumping, later Fjelkenbakken at Skaugum was inaugurated in 1891.

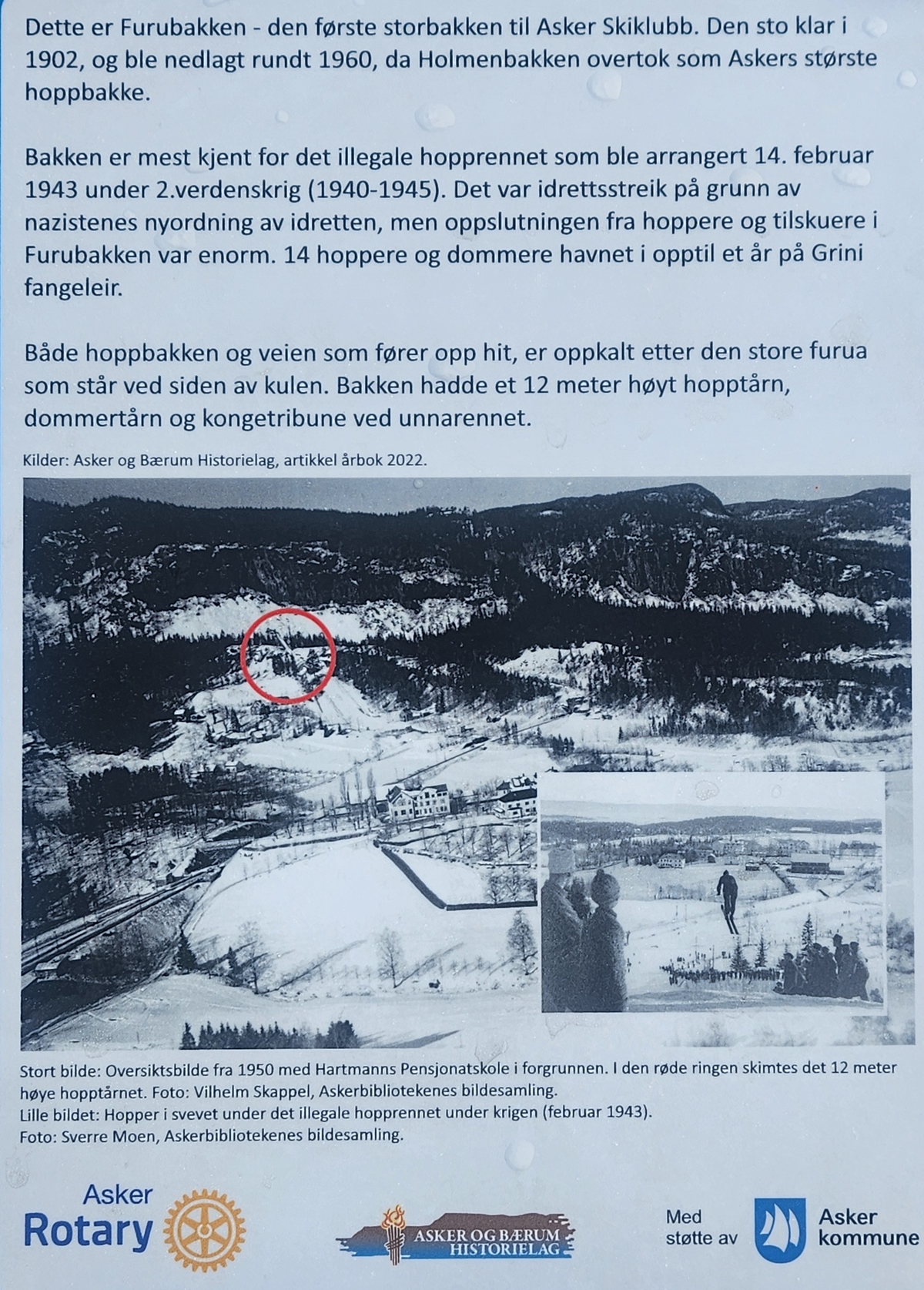

This was followed in 1902 by the inauguration of Furubakken, near Hvalstad station, which spectators liked to use to get there, and on what is now the street of the same name. The ski jump itself was named after a pine tree that stood at the front.

Furubakken was the most important ski jump in the town between 1902 and 1960 and was also important for women's ski jumping. After 1920, for example, a young woman named Kaja Aas repeatedly jumped there against boys of the same age, once surpassing the 30-metre mark. "The most remarkable thing about Kaja was not her style and elegance, but her courage, strength and body control when she was in the air," Brita Fossum remarked on the 50th anniversary of Skiklubb Asker in 1939.

Despite great competition from regular races in Aker, Drammen, Kongsberg, Hønefoss, Modum and, of course, Holmenkollen, the annual Askerrennet had great popularity. Until the First World War, up to 215 athletes took part in the events, often in front of an audience of up to 1000 spectators - in 1920 even 2000 spectators were counted. The greatest interest was in the Nordic Combined race for the challenge cup of Minister Wedel-Jarlsberg (until 1914 the Prince Carl Cup).

In 1923, the chairman of the club, Lassen-Urdahl, urged the construction of a stone inrun tower in order to be better prepared for changing freezing and thawing weather. The board was finally entrusted with this task. Just four years later, about 30 men set about the next reconstruction of the ski jump: The entire width of the ski jump was cleared of branches and levelled. The access road over the ski jump was levelled and improved. A scaffold about 5 metres high was erected at the top to increase the speed. This was erected in two sections so that there were now three different starting points and speeds - an early form of what we know today as starting gates.

In 1929, an even higher concrete inrun tower was built, while the landing slope was widened. The outrun was again lengthened, smoothed and cleared of bushes and shrubs. These corrections now made jumps beyond 45 metres possible. Again five years later, Hvalstad AIL applied to the municipality of Asker for permission to build another ski jump next to Furubakken, but this was rejected because they feared contamination of the water inflow.

However, this did not diminish the importance of Furubakken: From the mid-1930s onwards, even the crown prince's family was present at the jumps every year. The Askerrennet in 1938 was particularly memorable, as the 50-metre mark was broken twice for the first time. The report in the club magazine sounded accordingly euphoric: "Not only their own people were proud of the boys that day. You had the feeling that the whole village was proud of its sons." Because the year was also a good one financially for Asker Skiklubb, funds were used to further improve the ski jump: Master builder Kristian Solheim from Bærum raised the inrun tower to 12 metres, the ski jump table was moved backwards and the stem was raised. Thus the Furubakken had a critical point of 52 metres.

However, the 50-meter-mark was not broken until 1940, after the competitions had also been held in unfavourable weather conditions in the meantime. It was the beginning of a dark period for Norwegian sport and thus also for ski jumping. On 22 November 1940, the Norwegian National Sports Association and the Norwegian Workers' Sports Association were dissolved and their leaders dismissed. Federations, counties and teams went on a sports strike, which meant that organised sports and public competitions were stopped. This strike lasted until the end of the war, i.e. until May 1945. Through various decrees, the Nazis tried to organise sport through the Norwegian Sports Federation, but the sports strike was effective. In connection with the Nazification of sport, the Asker Ski Club was renamed Asker Idrettslag. In the process, the new leaders had initially rejected a very silly suggestion such as the Germanic-sounding name "Askar Idrottslag". However, the English-sounding suffix "Club" could not be used.

Illegal gatherings of athletes, so-called jøssing sports, were widespread in many sports and were organised in discrete forms in the countryside and in the forest. Skiing, athletics and orienteering were sports that eventually became regular competitions, and in many cases participants were also involved in resistance work. Overall, illegal sporting activity was relatively widespread, but took place partly in secret and only among insiders. Legal sport was hardly supported during the war, both by the athletes and the public, and was basically a rather boring affair. The so-called Norwegian championships were of a much lower standard, and only a few of the well-known athletes' names from the pre-war period were to be found in the results lists.

There were indeed many illegal ski jumping competitions in Norway during the war, but none had such serious consequences as the race on Furubakken on Sunday, 14th of February 1943. It was a large event with over a hundred participants and several hundred spectators. Eleven days later, fourteen participants were arrested and taken to Grini. Even people who were not present at all were arrested. Most of them were released relatively quickly, but Birger Ruud, who had previously been banned from sport for life by the Nazis, remained in prison for a year.

The first Askerrennet after the war on Sunday, 10th February 1946, was a big jumping event organised as a kind of reparation for the participants of 1943. They were to be given priority, as so many people had registered for the race that the number of participants had to be limited to 250. Ralph Tambs, who was murdered by the Nazis in the Natzweiler concentration camp on 23 April 1944, was also commemorated at this event. His parents donated the winner's cup in his honour.

In the summer and autumn of 1949, the ski jump was enlarged to its final size with a K-point of 60 metres. The profile was drafted by Per Fossum and the work was done with the help of two bulldozers. It was a good time to complete the ski jump for the 60th anniversary of the Asker Ski Club, because at the same time it was decided that Asker and Bærum would host the Norwegian Ski Championships, albeit not in 1949 as originally planned, but the following year, and Furubakken was to be the venue for the jumping part of the Nordic Combined event. This was then attended by between 3,000 and 4,000 spectators, which was to be an eternal record for Asker - just as Per Gjelten's 60 metres was to stand as a hill record.

After three years without an official competition, a jumping event was held again in 1954, but with considerably less jumper and spectator attendance beforehand. In the summer of the same year and autumn, the members carried out some beautification work on the ski jump. However, the 1955 jumping event could not take place due to a lack of snow. Then in 1956, 90 participants met again and jumped for the Tambs Cup. Per Thyness from Asker, who had won the previous competition, came closest to the hill record with 58 metres and consequently won the cup.

In 1956 the club received a very nice gift from one of Furubakken's closest neighbours, farmer Sigurd Solstad. It was a savings book of NOK. 2.000,-. This amount was to be used in future years to buy a prize that would go to the best jumper in the annual Furubakkrenn. The jumper had to be a junior (under 20) and from Askerbygda.

In 1957 the race was again cancelled due to lack of snow, but on Sunday 12 January 1958 it was again ready for a big training race (to replace the district race). However, once again the snow conditions did not play along. However, the club members did not want to give up: The ground was ploughed, the flat rolled and dragged, and the water was drained by about 4000 litres with the help of the fire brigade and an excellent neighbour, Skedsmo. He even ensured that heated water was available to irrigate the ground. The conditions during the race were nevertheless very difficult. Firstly, the landing slope was incredibly slippery and uneven, and secondly, it snowed heavily in both rounds. Overall, it was a very inconsistent race with a few bright spots. The biggest was Thorbjørn Yggeseth, who won clearly and stood the longest jump of the competition with 56.5 metres, which was an achievement in these conditions. There were no prizes, no programme and no entry fees, and almost no spectators. But a majority of the jumpers were there, and that was probably the main thing. For Asker Skiklubb, this competition was nevertheless the best advertisement, because at that time there was no other 60-metre hill in eastern Norway that could be used.

In 1959, to coincide with the club's 70th birthday, the competition programme went through as planned. Despite the inviting weather, only about 600 spectators turned up, so unfortunately the race was not a successful financial operation for the anniversary. One reason may have been the race in Nittedal at the same time, where the Oslo and Akers championships for the youngest classes were also held. In any case, Crown Prince Harald was present during the race, which was to be the last. The same was true for Gudtorm Helldal's 60 metres, which was to be the last hill record.

Both the ski jump scaffolding and the Furubakken judges' tower were demolished in the late summer of 1960. Both had become rotten and rather shaky due to the effects of the weather; the ski jump scaffolding for more than 20 years, the referee tower even longer. Another important reason was that on 6 March of the same year a terrible accident occurred on the Bekkelagsbakkene. The scaffolding of the middle jumps collapsed and 13 boys were injured, some of them seriously. The accident led to a number of ski jump scaffolds and towers being thoroughly checked and the Furubakken was blown up as a result. In 1961, Holmen Idrettsforening received a guarantee from the municipality for a loan of NOK 15,000 from Bergen Privatbank to rebuild Holmenbakken, which meant the final end for Furubakken.

Hill records K60 (Men):

Hill records K60 (Men):

Competitions:

Competitions:

Contact:

Contact:

Links:

Links:

Map:

Map:

Photo gallery:

Photo gallery:

Advertisement:

Dolní Bečva

Dolní Bečva Baiersbronn

Baiersbronn Sundsvall

Sundsvall  La Bresse

La Bresse

Post comment: